One discipline focuses primarily on the design, development, and operation of aircraft within Earth’s atmosphere. This field addresses aspects such as aerodynamics, propulsion, aircraft structures, and control systems for flight vehicles that operate primarily, or exclusively, in the air. Another, broader field extends the scope to include the design, development, and operation of spacecraft and other vehicles that operate in outer space. This encompasses a wider range of considerations, including orbital mechanics, spacecraft propulsion, life support systems, and the challenges of operating in the vacuum of space.

Understanding the nuances between these specializations is crucial for students choosing a career path, for industries seeking specific expertise, and for the public to appreciate the complexity of air and space travel. Historically, one specialization emerged first, driven by the invention and development of the airplane. As space exploration began, the other branch evolved to address the unique challenges of operating beyond Earth’s atmosphere.

This article will delve into specific areas of study, typical career paths, and the distinct technical challenges associated with each of these related, yet distinct, engineering fields. Furthermore, it will explore the overlap and potential areas of collaboration between experts in each field, highlighting the synergistic relationship between aeronautical pursuits and the broader exploration of aerospace.

Clarifying Specializations

Selecting the appropriate specialization requires careful consideration of career aspirations and interests. Understanding the distinction between focuses can guide educational and professional decisions.

Tip 1: Define Career Goals: Determine if the primary interest lies in designing and improving air-based vehicles, such as airplanes and helicopters, or if space exploration and satellite technology are more appealing. This clarifies the necessary skillset.

Tip 2: Evaluate Curriculum: Compare the course offerings of programs in each field. Aeronautical programs emphasize aerodynamics and aircraft design, while aerospace programs include orbital mechanics and spacecraft engineering.

Tip 3: Research Industry Trends: Investigate the current job market and future projections for each specialization. Identify industries and companies actively hiring in each field to assess opportunities.

Tip 4: Consider Technical Skills: Assess personal aptitude and enthusiasm for relevant technical skills. Aeronautical engineering requires strong knowledge of fluid dynamics, while aerospace engineering demands expertise in astrodynamics and materials science.

Tip 5: Explore Interdisciplinary Options: Recognize that some positions may benefit from a combination of both disciplines. Consider pursuing coursework or projects that bridge the gap between air and space vehicle design.

Tip 6: Understand Certification Requirements: Be aware of specific licensing or certification requirements for certain roles within each field. Professional registration may be necessary for specific engineering positions.

Tip 7: Seek Mentorship: Connect with professionals working in both fields to gain insights into their experiences and career paths. Mentors can provide valuable guidance on educational and professional choices.

Careful consideration of career goals, curriculum, industry trends, and technical skills is paramount. Seeking mentorship and understanding certification requirements further aids in making an informed decision.

The subsequent sections will provide deeper insights into the specific areas of expertise within each field, further assisting in distinguishing between these intertwined engineering disciplines.

1. Atmospheric Versus Space

The fundamental distinction between aeronautical and aerospace engineering resides in the operational environment: the atmosphere versus space. Aeronautical engineering is principally concerned with aircraft that operate within Earth’s atmosphere. This focus dictates the importance of aerodynamics, propulsion systems optimized for atmospheric flight, and structural considerations specific to withstanding atmospheric pressure and forces. The atmosphere itself is the medium through which the aircraft moves, influencing every aspect of its design and operation. An example is the design of wing shapes to maximize lift and minimize drag at varying altitudes and airspeeds. Aircraft engines, such as turbofans and turbojets, are designed to efficiently utilize atmospheric oxygen for combustion.

Aerospace engineering encompasses a broader scope, extending beyond the atmosphere to include spacecraft and other vehicles designed for operation in the vacuum of space. The absence of atmosphere necessitates a different approach to design and propulsion. Spacecraft require self-contained life support systems, radiation shielding, and propulsion systems that do not rely on atmospheric oxygen, such as rocket engines. The dynamics of orbital mechanics, including trajectory planning and satellite attitude control, become paramount. For instance, the design of a satellite’s solar panels and thermal control systems must account for the extreme temperature variations in space, which are absent in the atmosphere.

The division between atmospheric and space environments directly influences the skillsets and knowledge required in each discipline. Aeronautical engineers require deep understanding of fluid dynamics and atmospheric conditions. Aerospace engineers need expertise in vacuum environments, orbital mechanics, and the effects of space radiation. Understanding this fundamental difference is critical in differentiating career paths and educational requirements within these related engineering fields, underscoring how the operating environment dictates the design philosophy and operational challenges.

2. Vehicle Design Scope

Vehicle design scope serves as a primary delineator between aeronautical and aerospace engineering, dictating the specific engineering principles and design considerations employed. The range of vehicles encompassed by each field shapes the focus of research, development, and operational implementation.

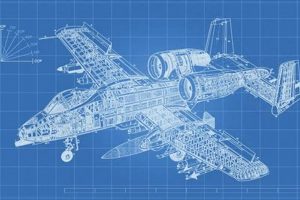

- Aircraft Design

Aeronautical engineering concentrates on the design of aircraft intended for atmospheric flight. This includes fixed-wing airplanes, rotary-wing helicopters, and lighter-than-air vehicles such as airships. Design considerations emphasize aerodynamic efficiency, structural integrity under atmospheric loads, and propulsion systems tailored for atmospheric conditions. The development of a new commercial airliner exemplifies this focus, requiring extensive wind tunnel testing and optimization of wing profiles to minimize drag and maximize lift at cruise altitudes.

- Spacecraft Design

Aerospace engineering broadens the vehicle design scope to include spacecraft designed for operation in the vacuum of space. This encompasses satellites, space probes, and crewed spacecraft. Design imperatives shift to address the challenges of the space environment, including radiation shielding, thermal management in the absence of convective heat transfer, and propulsion systems independent of atmospheric oxygen. An example is the design of a Mars rover, which must withstand extreme temperature fluctuations, operate autonomously, and communicate with Earth over vast distances.

- Missile and Rocket Design

Both aeronautical and aerospace engineering disciplines contribute to missile and rocket design, albeit with differing emphases. Aeronautical engineers may focus on the aerodynamic aspects of missile design for atmospheric flight, while aerospace engineers address the orbital mechanics and propulsion requirements for long-range ballistic missiles or space launch vehicles. The design of a multi-stage rocket, requiring the efficient staging of propulsion systems and the management of structural loads during launch, demonstrates the integration of these principles.

- Unmanned Aerial and Space Vehicle Design

The design of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and unmanned space vehicles (USVs) incorporates elements from both fields. UAV design often draws heavily on aeronautical principles for aerodynamic control and propulsion within the atmosphere, whereas USV design requires expertise in spacecraft systems and orbital maneuvering. The development of a high-altitude, long-endurance drone, capable of atmospheric flight for extended periods while carrying sophisticated surveillance equipment, merges the skill sets of both disciplines.

The vehicle design scope reflects the core competencies and application areas of each engineering field. Aeronautical engineering remains rooted in atmospheric flight, while aerospace engineering extends its reach into the domain of space exploration. While overlapping areas exist, such as missile design and unmanned vehicle development, the primary focus on either atmospheric or space-based vehicles dictates the specific engineering challenges and design priorities.

3. Orbital Mechanics Focus

Orbital mechanics, a branch of astrodynamics, is a pivotal area that significantly distinguishes aerospace engineering from aeronautical engineering. While aeronautical engineering concentrates on flight within Earth’s atmosphere, aerospace engineering incorporates the complexities of spacecraft motion in the vacuum of space, governed by celestial mechanics and gravitational forces. The extent to which orbital mechanics figures into the curriculum and practical applications sets these fields apart.

- Trajectory Design and Optimization

Aerospace engineers specializing in orbital mechanics focus on designing and optimizing spacecraft trajectories. This encompasses interplanetary missions, satellite deployment, and orbital transfer maneuvers. Understanding orbital mechanics is vital for calculating fuel requirements, minimizing transit times, and ensuring mission success. For example, the trajectory design for a mission to Mars involves calculating the optimal launch window, accounting for planetary positions and gravitational influences along the flight path. These considerations are largely absent in aeronautical engineering, which deals primarily with atmospheric flight paths.

- Satellite Orbit Determination and Prediction

Determining and predicting satellite orbits is a core task in aerospace engineering. This requires precise tracking data, sophisticated mathematical models, and algorithms to account for gravitational perturbations, atmospheric drag (for low Earth orbits), and solar radiation pressure. Accurate orbit determination is essential for satellite navigation systems, communication satellites, and Earth observation missions. For instance, predicting the precise location of a GPS satellite is crucial for accurate positioning data on Earth. Aeronautical engineering lacks this focus, as aircraft flight paths are predominantly influenced by aerodynamic forces within the atmosphere, not gravitational orbital parameters.

- Attitude Control and Stabilization

Maintaining a spacecraft’s attitude, or orientation, is another critical aspect of orbital mechanics. Aerospace engineers design and implement control systems to stabilize spacecraft, point instruments accurately, and perform orbital maneuvers. These control systems utilize reaction wheels, thrusters, and magnetic torquers to counteract external torques and maintain the desired orientation. The attitude control system of the James Webb Space Telescope, for example, must maintain extremely precise pointing accuracy to enable high-resolution observations. While aeronautical engineering addresses aircraft stability and control, the methods and challenges differ significantly due to the presence of aerodynamic forces.

- Space Debris Mitigation

Orbital mechanics plays a crucial role in mitigating the risk of space debris. Aerospace engineers develop strategies to track, characterize, and avoid collisions with space debris. This involves predicting the trajectories of debris objects, assessing collision probabilities, and implementing avoidance maneuvers when necessary. The increasing amount of space debris poses a significant threat to operational satellites and crewed spacecraft. Aeronautical engineering does not directly address this issue, as it is specific to the space environment.

These facets of orbital mechanics highlight its central role in aerospace engineering. While aeronautical engineering focuses on atmospheric flight, aerospace engineering extends its reach into the vacuum of space, where the laws of celestial mechanics govern the motion of spacecraft. The ability to design trajectories, determine orbits, control attitude, and mitigate space debris are all essential skills for aerospace engineers working in the space domain. This emphasis on orbital mechanics firmly differentiates aerospace engineering from its aeronautical counterpart, showcasing the distinct knowledge and skillsets required for each discipline.

4. Aerodynamics Emphasis

Aerodynamics, the study of air in motion, constitutes a critical area of focus that differentiates aeronautical engineering from aerospace engineering. While both fields require a foundational understanding of aerodynamics, the degree of emphasis and the specific applications vary significantly. Aeronautical engineering places a greater emphasis on aerodynamics due to its direct impact on aircraft performance, stability, and control within Earth’s atmosphere. The following points detail this disparity.

- Airfoil Design and Optimization

Aeronautical engineering places substantial emphasis on airfoil design and optimization for specific flight conditions. Airfoils, the cross-sectional shape of wings, are engineered to maximize lift and minimize drag at various airspeeds and altitudes. Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations and wind tunnel testing are extensively used to refine airfoil designs. An example is the development of supercritical airfoils for commercial airliners, enabling efficient high-speed flight. In contrast, while aerospace engineers also utilize airfoil principles, their focus broadens to include spacecraft aerodynamics during atmospheric reentry, where heating and extreme flow conditions are paramount.

- Boundary Layer Control

Boundary layer control, the manipulation of the thin layer of air adjacent to an aircraft’s surface, is crucial for reducing drag and improving lift. Aeronautical engineers develop techniques such as boundary layer suction and blowing to delay or prevent flow separation, thereby enhancing aerodynamic efficiency. Laminar flow control wings, designed to maintain smooth airflow over a larger portion of the wing surface, exemplify this emphasis. Aerospace engineering addresses boundary layer effects during reentry, but the extreme conditions and high speeds necessitate different strategies focused on managing heat transfer and aerodynamic forces.

- High-Lift Devices

Aeronautical engineering relies heavily on high-lift devices, such as flaps and slats, to increase lift during takeoff and landing. These devices alter the airfoil shape and increase the wing’s effective surface area, enabling aircraft to operate at lower speeds. The design and optimization of high-lift systems are critical for ensuring safe and efficient low-speed performance. While aerospace vehicles may utilize similar devices for atmospheric flight phases, the emphasis shifts to other methods, such as reaction control systems, for maneuvering in space.

- Aircraft Stability and Control

Aerodynamic principles are fundamental to aircraft stability and control. Aeronautical engineers design control surfaces, such as ailerons, elevators, and rudders, to manipulate aerodynamic forces and moments, allowing pilots to control the aircraft’s attitude and trajectory. Stability analysis and control system design are essential for ensuring safe and predictable flight characteristics. While aerospace engineers also address stability and control, their focus extends to spacecraft attitude control using reaction wheels, thrusters, and other non-aerodynamic means in the vacuum of space.

The pronounced emphasis on aerodynamics in aeronautical engineering stems from the discipline’s core focus on atmospheric flight. While aerospace engineering incorporates aerodynamic principles, its scope encompasses a broader range of phenomena, including orbital mechanics, space propulsion, and spacecraft systems. The specific applications and design considerations within each field reflect their distinct operational environments and engineering priorities, thereby clearly demonstrating a key aspect of their differences.

5. Propulsion System Variety

The diversity of propulsion systems constitutes a significant differentiating factor between aerospace and aeronautical engineering. Aeronautical engineering primarily concerns itself with propulsion systems designed for operation within Earth’s atmosphere. These systems typically rely on air-breathing engines, such as turbojets, turbofans, and turboprops, which utilize atmospheric oxygen for combustion. The performance characteristics of these engines are heavily influenced by factors such as air density, temperature, and airspeed. The development of more fuel-efficient turbofans for commercial airliners exemplifies this specialization, driving advancements in compressor design, turbine materials, and combustion efficiency. The operational altitude and speed range of air-breathing engines limit their applicability beyond the atmospheric boundary.

Aerospace engineering, in contrast, encompasses a much broader range of propulsion technologies, including those designed for operation in the vacuum of space. These systems include rocket engines, which carry their own oxidizer and are capable of generating thrust independently of an atmosphere. Rocket engine designs vary widely, encompassing solid-propellant rockets, liquid-propellant rockets, and hybrid rockets. Moreover, aerospace engineers also work with non-chemical propulsion systems, such as ion thrusters and solar sails, which offer high specific impulse for long-duration space missions, despite generating relatively low thrust. The selection of a specific propulsion system depends on mission requirements, such as thrust-to-weight ratio, specific impulse, and mission duration. For example, a deep-space probe may utilize ion thrusters for efficient long-duration travel, while a launch vehicle requires high-thrust rocket engines to escape Earth’s gravity.

The variety of propulsion systems employed necessitates distinct skill sets and areas of expertise within each engineering discipline. Aeronautical engineers require in-depth knowledge of thermodynamics, fluid mechanics, and combustion, with a focus on optimizing engine performance within atmospheric conditions. Aerospace engineers, conversely, must possess a comprehensive understanding of rocket propulsion principles, orbital mechanics, and spacecraft systems integration. The need to design, analyze, and integrate diverse propulsion systems for both atmospheric and space environments thus underscores a key difference between aerospace and aeronautical engineering, driving specialization in distinct areas of propulsion technology and application.

6. Material Science Breadth

The scope of materials science expertise demanded by aerospace engineering significantly exceeds that typically required in aeronautical engineering, primarily due to the extreme environmental conditions encountered in space. While both fields necessitate a strong foundation in material properties and structural integrity, aerospace applications impose additional constraints related to thermal management, radiation shielding, and long-term durability in a vacuum. This broader materials science landscape represents a critical aspect of the distinction between the two disciplines. For instance, aeronautical engineers selecting materials for an aircraft fuselage prioritize factors such as strength-to-weight ratio, corrosion resistance, and fatigue life under cyclic loading. Aerospace engineers selecting materials for a satellite must address these factors in addition to the effects of extreme temperature variations, prolonged exposure to ultraviolet and ionizing radiation, and the potential for micrometeoroid impacts. These added complexities result in a markedly different material selection process and necessitate expertise in a wider range of materials, including specialized polymers, composites, and high-temperature alloys.

One practical example of this difference lies in the selection of materials for thermal protection systems (TPS) on spacecraft. The Space Shuttle, for instance, employed a diverse range of materials for its TPS, including reinforced carbon-carbon (RCC) for leading edges and nose cap, high-temperature reusable surface insulation (HRSI) tiles, and flexible reusable surface insulation (FRSI). These materials were specifically chosen to withstand the extreme heat generated during atmospheric reentry. Aeronautical applications rarely encounter such extreme thermal loads, allowing for the use of more conventional materials. Furthermore, the long-term durability requirements for spacecraft materials pose unique challenges. Materials used in space must resist degradation from prolonged exposure to the space environment, including atomic oxygen erosion in low Earth orbit and radiation damage throughout the solar system. This requires extensive testing and characterization of materials under simulated space conditions, something less critical in the design of most aircraft. The James Webb Space Telescope, with its complex sunshield constructed from multiple layers of Kapton coated with aluminum and silicon, highlights the extreme measures taken to control temperature and protect sensitive instruments from solar radiation, a testament to the specialized material science knowledge required for aerospace projects.

In summary, the broader scope of materials science in aerospace engineering stems directly from the harsh operational environment of space. The need to withstand extreme temperatures, radiation, and vacuum conditions necessitates expertise in a wider range of materials and specialized testing methodologies. While aeronautical engineering benefits from advancements in materials science, its application remains focused on optimizing performance within the relatively benign confines of Earth’s atmosphere. The practical implications of this difference are significant, impacting material selection, design considerations, and the overall complexity of engineering projects in each field. Future advancements in materials science will undoubtedly continue to shape both aerospace and aeronautical engineering, driving innovation in both atmospheric and space-based vehicles, but the specific material challenges and solutions will remain distinct, reinforcing the fundamental differences between these two interconnected disciplines.

7. Control Systems Range

The range of control systems employed in aeronautical and aerospace engineering highlights a key divergence between the fields. While both disciplines rely on control systems to govern vehicle stability, maneuverability, and overall performance, the complexity, operating environment, and specific challenges differ significantly. The scope of control systems, therefore, becomes a fundamental marker of specialization.

- Aircraft Flight Control Systems

Aeronautical engineering focuses on flight control systems designed for atmospheric flight. These systems manipulate aerodynamic surfaces, such as ailerons, elevators, and rudders, to control the aircraft’s orientation and trajectory. Stability augmentation systems, autopilot functions, and fly-by-wire technology are integral components of modern aircraft flight control. The design of a flight control system for a commercial airliner necessitates precise control over pitch, roll, and yaw axes, ensuring passenger comfort and safety throughout the flight envelope. The reliance on aerodynamic forces and sensors that measure air pressure and airspeed distinguishes this domain.

- Spacecraft Attitude Control Systems

Aerospace engineering extends control system design to encompass spacecraft attitude control systems, which maintain a spacecraft’s desired orientation in the vacuum of space. These systems employ reaction wheels, control moment gyros, magnetic torquers, and thrusters to counteract external torques and stabilize the spacecraft. The attitude control system of a satellite, for example, must maintain precise pointing accuracy for communication or Earth observation purposes. The absence of aerodynamic forces necessitates alternative control methods and sensors, such as star trackers and sun sensors, to determine spacecraft orientation. The complexity and precision requirements of these systems often exceed those found in aeronautical applications.

- Guidance and Navigation Systems

Both aeronautical and aerospace engineering utilize guidance and navigation systems to determine a vehicle’s position and velocity and to guide it along a desired trajectory. However, the specific technologies and algorithms employed differ depending on the operating environment. Aircraft navigation systems rely on inertial navigation systems (INS), GPS, and radio navigation aids to determine position and guide the aircraft. Spacecraft navigation systems utilize similar technologies but also incorporate star trackers, ranging measurements, and sophisticated orbital determination algorithms to navigate in the vacuum of space. Interplanetary missions, such as the Voyager probes, require highly accurate guidance and navigation systems to reach their distant destinations, demonstrating the sophisticated capabilities of aerospace guidance technology.

- Robotics and Automation

The integration of robotics and automation further expands the scope of control systems in both aeronautical and aerospace engineering. Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and unmanned spacecraft rely on autonomous control systems to perform complex tasks without direct human intervention. These systems incorporate advanced sensors, artificial intelligence algorithms, and sophisticated control strategies to enable autonomous flight, navigation, and payload operation. The development of autonomous landing systems for UAVs and the design of robotic arms for space exploration exemplify the integration of robotics and control systems in these fields. The level of autonomy and the challenges associated with operating in remote or hazardous environments underscore the advanced capabilities of these systems.

The range of control systems encountered in aeronautical and aerospace engineering reflects the distinct operational environments and engineering challenges associated with each field. From aircraft flight control systems relying on aerodynamic surfaces to spacecraft attitude control systems operating in the vacuum of space, the specific technologies, algorithms, and design considerations vary significantly. This diversity in control systems represents a fundamental aspect of the distinction between these two intertwined engineering disciplines, influencing the knowledge and skillsets required for success in each field.

Frequently Asked Questions

This section addresses common inquiries regarding the distinct characteristics of aerospace engineering and aeronautical engineering. The aim is to clarify prevalent misconceptions and provide a concise overview of the key differentiating factors.

Question 1: What constitutes the primary distinction between aerospace engineering and aeronautical engineering?

The primary distinction lies in the operational environment. Aeronautical engineering focuses on the design, development, and operation of aircraft within Earth’s atmosphere. Aerospace engineering broadens the scope to include spacecraft and other vehicles operating in outer space.

Question 2: Does a degree in aeronautical engineering limit career opportunities to only aircraft-related industries?

While an aeronautical engineering degree emphasizes aircraft, the foundational knowledge of aerodynamics, propulsion, and structures is transferable to other industries. These skills can be relevant in automotive engineering, wind energy, and even some aspects of civil engineering.

Question 3: Is a higher degree, such as a Master’s or Doctorate, necessary for specialization in either aerospace or aeronautical engineering?

A higher degree is not strictly necessary for entry-level positions. However, advanced degrees often provide specialized knowledge and research experience that can enhance career prospects, particularly in research and development roles.

Question 4: Are there specific software or programming languages that are essential for both aerospace and aeronautical engineers?

Yes. Common software tools include CAD/CAM software for design, CFD software for aerodynamic simulations, and FEA software for structural analysis. Proficiency in programming languages such as MATLAB, Python, and FORTRAN is also highly valuable.

Question 5: Do aerospace and aeronautical engineers typically work in isolation, or is there collaboration between the two fields?

Collaboration is common, particularly in projects involving hypersonic vehicles, missile systems, and atmospheric reentry technologies. Experts from both fields often contribute their specialized knowledge to achieve project goals.

Question 6: What are the most critical skills for success in aerospace and aeronautical engineering beyond technical expertise?

Beyond technical skills, crucial attributes include strong problem-solving abilities, teamwork and communication skills, project management experience, and a commitment to continuous learning and adaptation to technological advancements.

In summary, while aerospace and aeronautical engineering share common foundations, their distinct operational environments and specific challenges require specialized knowledge and skillsets. A clear understanding of these differences is essential for informed career planning and professional development.

The subsequent section will explore potential career paths within each field, further clarifying the distinct opportunities available to graduates.

Conclusion

The preceding analysis has illuminated the multifaceted nature of aerospace engineering and aeronautical engineering difference. While both disciplines share fundamental principles of physics and engineering, their respective applications and areas of specialization diverge significantly. Aeronautical engineering maintains a focused approach on atmospheric flight, optimizing aircraft design, propulsion, and control systems for operation within Earth’s atmosphere. Aerospace engineering extends its scope beyond the atmosphere, encompassing spacecraft design, orbital mechanics, and the challenges of operating in the vacuum of space. The delineation in material science demands and control systems range further accentuates this divergence.

Comprehending this aerospace engineering and aeronautical engineering difference is paramount for students navigating career paths, industries seeking targeted expertise, and policymakers shaping the future of air and space travel. Continued advancements in both domains are vital for both the advancement of transportation and the ongoing exploration of our universe. A clear understanding of these fields allows for informed choices and strategic investments that propel innovation within both domains.