The relative difficulty of academic disciplines is a frequent subject of debate. Comparing the rigor of studying the design, development, and testing of aircraft and spacecraft to the science and art of diagnosing, treating, and preventing disease presents significant challenges. Each field demands distinct skill sets, approaches to problem-solving, and cognitive strengths. The perception of which is more challenging often depends on individual aptitudes and preferences, as well as the specific curricula and institutions involved.

The significance of both fields is undeniable. Aerospace engineering contributes to advancements in transportation, communication, exploration, and defense. Medicine is essential for maintaining and improving human health and well-being. Historically, both disciplines have undergone periods of rapid innovation, driven by societal needs and technological breakthroughs. These evolutions continue to shape the requirements and expectations for professionals in each domain.

This analysis will explore factors contributing to the perceived difficulty of each field, including the required coursework, the nature of the problem-solving involved, and the pressures associated with professional practice. It will also consider the different career paths and the personal attributes that tend to lead to success in each area.

Considerations Regarding the Relative Rigor of Aerospace Engineering and Medicine

Assessing the difficulty of either discipline necessitates a comprehensive understanding of the distinct demands inherent in each field. The following points offer a structured approach to evaluating the academic and professional challenges.

Tip 1: Evaluate Foundational Aptitude. Success in aerospace engineering relies heavily on a strong foundation in mathematics, physics, and computer science. Medicine, while incorporating scientific principles, emphasizes biology, chemistry, and a capacity for understanding complex biological systems.

Tip 2: Analyze Curriculum Depth and Breadth. Aerospace engineering curricula often involve specialized courses in aerodynamics, propulsion, and structural mechanics. Medicine requires extensive study of anatomy, physiology, pharmacology, and pathology.

Tip 3: Compare Problem-Solving Approaches. Aerospace engineering typically involves quantitative problem-solving, utilizing simulations and models to predict system behavior. Medicine relies on diagnostic reasoning, pattern recognition, and clinical judgment to address individual patient needs.

Tip 4: Acknowledge Ethical Considerations. While both fields involve ethical considerations, medicine places a particularly strong emphasis on patient confidentiality, informed consent, and end-of-life care. Aerospace engineering ethics frequently centers on safety, environmental impact, and responsible use of technology.

Tip 5: Recognize Career Trajectory Pressures. The path to becoming a licensed physician involves rigorous training through residency programs, often demanding long hours and significant personal sacrifice. Aerospace engineers may face pressure related to project deadlines, budget constraints, and safety regulations.

Tip 6: Consider Personal Learning Style. Individuals who thrive in analytical, detail-oriented environments may find aerospace engineering more appealing. Those who possess strong interpersonal skills, empathy, and a genuine interest in helping others may be better suited for medicine.

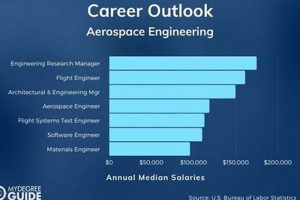

Tip 7: Research Employment Outlook. Assess the availability of job opportunities and the potential for career advancement in each field. The demand for both aerospace engineers and medical professionals varies depending on geographical location, specialization, and economic conditions.

Careful consideration of these factors allows for a more informed perspective on the challenges associated with each domain. There isn’t a universally “harder” path; rather, individual strengths and weaknesses will influence the perceived difficulty and ultimately, the suitability for either profession.

The choice between these fields should be based on a thorough self-assessment and a realistic understanding of the demands and rewards associated with each career path.

1. Mathematical Proficiency

Mathematical proficiency constitutes a cornerstone of aerospace engineering, significantly influencing the perceived difficulty of the discipline when compared to medicine. Its pervasive role in the analysis, design, and optimization of aerospace systems underscores its importance. The level and depth of mathematical application directly impact the complexity and challenges encountered within the field.

- Calculus and Differential Equations

Aerospace engineering relies heavily on calculus and differential equations to model fluid dynamics, structural mechanics, and control systems. Accurately predicting the behavior of aircraft and spacecraft necessitates solving complex equations, requiring a robust understanding of these mathematical principles. The ability to formulate and solve these equations directly affects the engineer’s capacity to design safe and efficient aerospace vehicles. Inability to master these skills can make the degree exponentially more challenging.

- Linear Algebra

Linear algebra provides the framework for analyzing structural stability, performing finite element analysis, and implementing control algorithms. Manipulating matrices and vectors is essential for solving systems of equations that describe the behavior of complex aerospace structures. A deficiency in linear algebra can hinder the ability to assess the integrity and performance of critical aerospace components. Understanding this component can affect safety and performance.

- Probability and Statistics

Probabilistic methods and statistical analysis are critical for assessing risk, estimating reliability, and designing robust systems. Understanding probability distributions and statistical inference is essential for quantifying uncertainties and making informed decisions in aerospace engineering. For instance, it is necessary to be able to determine the probability of failure for different engine systems. A weakness in these areas can compromise the ability to ensure the safety and reliability of aerospace systems.

- Numerical Methods

Many aerospace engineering problems do not have analytical solutions and require numerical methods for approximation. Algorithms like the finite difference method and the finite element method are essential for solving complex equations on computers. A strong grasp of numerical methods is necessary to utilize commercial software and to develop custom tools for aerospace analysis. Failure to understand these can lead to inaccurate models, which can then lead to significant errors in engineering design.

The degree to which mathematical proficiency is emphasized within aerospace engineering contributes substantially to its perceived difficulty. While medicine also requires quantitative reasoning, the depth and breadth of mathematical applications within aerospace engineering are often more extensive. The ability to abstract, model, and solve complex mathematical problems is therefore a critical determinant of success and a key differentiator in assessing the relative challenges of each discipline. The weight of these areas can be a key point to ‘is aerospace engineering harder than medicine’ question.

2. Diagnostic Skill

Diagnostic skill, though traditionally associated with medicine, holds a distinct, albeit different, relevance when considering the relative difficulty of aerospace engineering. While medical diagnostics focus on identifying and treating ailments within a biological system, aerospace engineering diagnostics center on pinpointing failures and optimizing performance within complex mechanical and electronic systems. This disparity in focus is crucial to understanding the comparative rigor of the two disciplines.

- System Failure Analysis

Aerospace engineering diagnostics involve meticulous analysis of system failures. For example, if a satellite experiences an unexpected loss of power, engineers must diagnose the cause, which could range from solar panel degradation to battery malfunction to software anomalies. This requires a deep understanding of interconnected systems and the ability to methodically rule out potential causes. In comparison to medical diagnostics, the “patient” is a machine, and the diagnostic process often relies heavily on instrumentation data and simulations. The lack of direct intuition adds a layer of complexity.

- Non-Destructive Testing

Non-destructive testing (NDT) techniques are essential for diagnosing potential structural weaknesses in aircraft or spacecraft without causing damage. Methods such as ultrasonic testing, radiography, and eddy current testing are used to detect cracks, corrosion, and other defects. Interpreting NDT results requires specialized knowledge and experience. This contrasts with medical imaging, where a radiologist interprets images of the human body. However, aerospace NDT involves sophisticated signal processing and material science, presenting unique diagnostic challenges.

- Performance Optimization

Diagnostics in aerospace engineering also encompass performance optimization. For example, analyzing flight data to identify areas where fuel efficiency can be improved or diagnosing aerodynamic inefficiencies through computational fluid dynamics simulations. This requires a different skill set than failure analysis, focusing on identifying subtle deviations from optimal performance rather than catastrophic failures. Similar to preventative medicine, it aims at improving performance and extending lifespan.

- Fault Tolerance Design

A critical aspect of aerospace engineering is designing systems with fault tolerance. This involves anticipating potential failures and incorporating redundancy or backup systems to mitigate their impact. Diagnosing potential vulnerabilities in fault-tolerant systems requires a proactive approach, anticipating failure modes and evaluating the effectiveness of mitigation strategies. The “diagnostics” is upfront, making this aspect a critical difference in diagnostic skill.

While the term “diagnostic skill” is primarily associated with medicine, aerospace engineering demands a comparable ability to identify, analyze, and resolve issues within complex systems. The nature of the “patient” and the diagnostic tools employed differ significantly, influencing the cognitive demands and skills required. Whether one finds aerospace diagnostics or medical diagnostics more challenging is largely dependent on individual aptitudes and preferences, emphasizing that the perception of difficulty varies from person to person when contemplating ‘is aerospace engineering harder than medicine’.

3. System Complexity

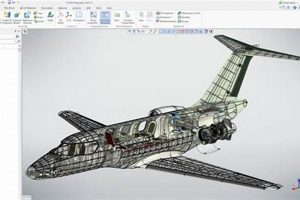

The inherent complexity of aerospace systems significantly contributes to the perception of aerospace engineering as a demanding discipline, thereby influencing the assessment of “is aerospace engineering harder than medicine.” Aerospace vehicles, be they aircraft or spacecraft, are characterized by the integration of numerous interconnected subsystems, each contributing to overall functionality and performance. The intricate nature of these systems necessitates a comprehensive understanding of diverse engineering principles and their interactions. A single alteration in one subsystem can propagate through the entire vehicle, creating a cascade of effects that require careful consideration. For example, a change in wing geometry affects aerodynamics, structural loading, control system parameters, and propulsion requirements. This interdependence elevates the complexity of the design process and subsequent operation.

The impact of system complexity is evident in real-world scenarios. The development of the Space Shuttle, for instance, exemplified the challenges of integrating diverse technologies into a single vehicle. The propulsion system, thermal protection system, and orbital maneuvering system all demanded sophisticated engineering solutions and precise coordination. Failures in any of these systems could have catastrophic consequences, highlighting the critical importance of understanding and managing system complexity. Similarly, the design of modern commercial aircraft involves balancing competing requirements for fuel efficiency, passenger comfort, and safety, demanding a multidisciplinary approach to engineering. The management of system complexity extends beyond the initial design phase. Throughout the operational life cycle, continuous monitoring and maintenance are necessary to ensure the continued safe and efficient operation of aerospace vehicles. This necessitates a highly skilled workforce capable of diagnosing and resolving complex technical issues.

In summary, the system complexity inherent in aerospace engineering creates significant challenges in design, development, and operation. The need to integrate diverse technologies, manage interdependencies, and ensure safety under extreme conditions contributes to the perception of aerospace engineering as a highly demanding field. While medicine deals with the complexities of the human body, the engineered systems in aerospace present a different type of challenge one of precise control, predictable performance, and absolute reliability. This distinctive nature of the complexity involved helps delineate the parameters of the “is aerospace engineering harder than medicine” question.

4. Ethical Scrutiny

Ethical scrutiny, while a central tenet of medical practice, also exerts significant influence on aerospace engineering, though often manifested in different forms. The necessity to adhere to stringent ethical standards in both fields contributes to the overall challenges and, consequently, the perception of comparative difficulty. Aerospace engineering’s ethical dimensions are intricately linked to safety, environmental impact, and the potential for misuse of technology, factors that elevate the responsibilities and demands placed upon professionals in this discipline.

- Safety and Reliability

The primary ethical concern in aerospace engineering is ensuring the safety and reliability of aircraft and spacecraft. Engineers are responsible for designing systems that minimize the risk of accidents and protect human lives. This necessitates rigorous testing, meticulous documentation, and adherence to strict regulatory standards. Failures in aerospace systems can have catastrophic consequences, underscoring the importance of ethical decision-making throughout the design and development process. The potential for loss of life adds a significant ethical weight to aerospace engineering, similar to the ethical burdens faced by medical professionals.

- Environmental Impact

Aerospace activities can have a significant impact on the environment, contributing to air pollution, noise pollution, and greenhouse gas emissions. Engineers have a responsibility to minimize these negative effects through the development of more sustainable technologies and practices. This includes designing more fuel-efficient aircraft, developing alternative propulsion systems, and reducing the environmental footprint of aerospace operations. Balancing performance requirements with environmental concerns presents a complex ethical challenge, forcing engineers to make trade-offs and consider the long-term consequences of their decisions. Ethically, this mirrors the decisions that doctors and the healthcare system face, weighing immediate benefits against potential long term consequences.

- Dual-Use Technology

Many aerospace technologies have dual-use capabilities, meaning they can be used for both civilian and military purposes. This raises ethical concerns about the potential for these technologies to be used for harmful or aggressive purposes. Engineers must carefully consider the potential implications of their work and avoid contributing to the development of weapons or technologies that could be used to violate human rights. The ethical responsibility to prevent the misuse of technology adds a layer of complexity to aerospace engineering, demanding careful consideration of the potential consequences of innovation.

- Responsible Innovation

The rapid pace of technological advancement in aerospace engineering raises ethical questions about responsible innovation. Engineers must consider the potential societal and economic impacts of new technologies and ensure that they are developed and deployed in a way that benefits humanity. This requires engaging in open dialogue with stakeholders, addressing potential risks, and promoting equitable access to the benefits of aerospace technology. Responsible innovation demands a proactive and ethical approach to engineering, ensuring that technological progress aligns with societal values.

The ethical considerations inherent in aerospace engineering, while distinct from those in medicine, are nonetheless substantial and contribute to the perceived difficulty of the field. The need to balance safety, environmental impact, and the potential for misuse of technology demands a high level of ethical awareness and responsible decision-making. These ethical dimensions, combined with the technical challenges of the discipline, contribute to the overall complexity and demands placed on aerospace engineers. This consideration affects the analysis when the question “is aerospace engineering harder than medicine?” is asked.

5. Specialized Knowledge

The breadth and depth of specialized knowledge required in both aerospace engineering and medicine play a significant role in the subjective assessment of comparative difficulty. The distinct nature of this expertise in each field shapes the challenges encountered, influencing the perception of ‘is aerospace engineering harder than medicine’ based on individual aptitude and learning styles.

- Aerodynamics and Fluid Mechanics

Aerospace engineering demands a thorough understanding of aerodynamics and fluid mechanics, encompassing concepts like lift, drag, boundary layers, and compressible flow. Designing efficient and stable aircraft requires mastery of these principles, often involving advanced mathematical modeling and computational simulations. For example, the design of a new aircraft wing necessitates extensive analysis of airflow patterns to minimize drag and maximize lift at various speeds and altitudes. The depth of this specialized knowledge, often involving highly complex equations and simulations, can be particularly challenging for those without a strong mathematical background. It is an example of ‘is aerospace engineering harder than medicine’.

- Anatomy and Physiology

Medicine necessitates comprehensive knowledge of anatomy and physiology, requiring an in-depth understanding of the structure and function of the human body. This includes intricate knowledge of organ systems, cellular processes, and the interactions between different parts of the body. For instance, diagnosing a heart condition requires detailed knowledge of cardiac anatomy, electrophysiology, and the physiological mechanisms underlying various diseases. The sheer volume of information, coupled with the complexity of biological systems, can be overwhelming and necessitates a significant commitment to memorization and conceptual understanding. Mastering these principles and applying them in diagnosis and treatment forms a cornerstone of medical practice.

- Materials Science and Structural Mechanics

Aerospace engineering requires specialized knowledge of materials science and structural mechanics to design lightweight, strong, and durable aircraft and spacecraft. This involves understanding material properties, stress analysis, and the behavior of structures under various loads and environmental conditions. Selecting the appropriate materials for a specific application, such as the skin of an aircraft or the heat shield of a spacecraft, requires careful consideration of factors like strength-to-weight ratio, temperature resistance, and cost. The specialized knowledge required can directly affect the safety and efficiency of aerospace systems.

- Pharmacology and Therapeutics

Medicine necessitates an extensive knowledge of pharmacology and therapeutics, encompassing the mechanisms of action, side effects, and interactions of various drugs. Prescribing the appropriate medication for a given condition requires a thorough understanding of these principles, as well as individual patient factors. For instance, treating a bacterial infection requires selecting an antibiotic that is effective against the specific bacteria, while also considering the patient’s allergies, medical history, and potential drug interactions. The need for continuous learning and adaptation in response to new drugs and therapies adds to the demands of medical practice.

The specific knowledge bases needed in both disciplines are undeniably immense, highlighting their specialized nature. Each has complexities and unique hurdles. Therefore, whether ‘is aerospace engineering harder than medicine’ remains a matter of individual disposition and strengths as specialized mastery is demanded from both, albeit in differing arenas.

6. Time Commitment

The extensive time commitment associated with both aerospace engineering and medicine significantly influences perceptions of difficulty and contributes to the ongoing discourse surrounding “is aerospace engineering harder than medicine.” The demanding schedules, rigorous training, and continuous learning requirements inherent in both fields often necessitate substantial personal sacrifices and a dedication beyond typical working hours. The sheer volume of material to be mastered, coupled with the pressure to perform under stringent deadlines and exacting standards, can place a significant strain on individuals pursuing these careers. This time commitment acts as a key component in evaluating the overall demands of each discipline.

In aerospace engineering, demanding project deadlines, complex simulations, and the iterative nature of design and testing frequently result in long working hours. For instance, during the development of a new aircraft, engineers may face intense periods of analysis, modeling, and prototyping, requiring them to work evenings and weekends to meet crucial milestones. Similarly, medical professionals endure years of rigorous training, including medical school, residency, and fellowships, characterized by demanding clinical rotations and extensive on-call duties. Residents often work over 80 hours per week, balancing patient care, administrative tasks, and continuing education. The intensity of these schedules can lead to burnout and contribute to the perception of medicine as an exceedingly challenging field. Furthermore, the need for continuous learning in both disciplines adds to the time commitment. Aerospace engineers must stay abreast of advancements in materials science, aerodynamics, and propulsion systems, while medical professionals must remain current on the latest medical research, treatment protocols, and technological innovations. Failure to dedicate sufficient time to continuing education can jeopardize professional competence and negatively impact patient outcomes or engineering designs.

Ultimately, the significant time commitment demanded by both aerospace engineering and medicine underscores the demanding nature of these professions. While the specific tasks and responsibilities may differ, the need for sustained effort, unwavering dedication, and continuous learning is a common thread. Individuals contemplating careers in either field should carefully consider the lifestyle implications and be prepared to dedicate a substantial portion of their time and energy to achieving professional success. The perception of whether “is aerospace engineering harder than medicine” often hinges on an individuals capacity to manage the demands of such significant time investment and workload.

Frequently Asked Questions

This section addresses common queries regarding the perceived difficulty of aerospace engineering relative to medicine. The intent is to provide objective information to aid in understanding the demands of each field.

Question 1: What are the fundamental differences in the skill sets required for aerospace engineering and medicine?

Aerospace engineering necessitates strong analytical skills, particularly in mathematics and physics, for designing and analyzing complex systems. Medicine requires robust diagnostic and interpersonal skills, coupled with a deep understanding of biological systems and patient care.

Question 2: How does the curriculum structure contribute to the perceived difficulty of each field?

Aerospace engineering curricula often emphasize specialized coursework in areas like aerodynamics, propulsion, and structural mechanics, requiring a high degree of technical proficiency. Medical curricula involve extensive study of anatomy, physiology, pharmacology, and pathology, demanding significant memorization and application of knowledge to clinical scenarios.

Question 3: What are the primary ethical considerations in aerospace engineering compared to medicine?

Aerospace engineering ethics frequently revolve around safety, environmental impact, and the responsible use of technology, particularly concerning dual-use applications. Medical ethics primarily concern patient confidentiality, informed consent, and end-of-life care, emphasizing the well-being and autonomy of the individual.

Question 4: How does the workload and time commitment compare between aerospace engineering and medicine?

Both fields involve demanding workloads and significant time commitments. Aerospace engineers often face intense project deadlines and complex design challenges, while medical professionals endure long hours during residency and face continuous on-call responsibilities.

Question 5: What types of problem-solving approaches are utilized in each discipline?

Aerospace engineering typically employs quantitative problem-solving, relying on simulations, modeling, and numerical analysis to predict system behavior. Medicine emphasizes diagnostic reasoning, pattern recognition, and clinical judgment to address individual patient needs and develop treatment plans.

Question 6: How does career advancement potential differ between aerospace engineering and medicine?

Career advancement in aerospace engineering often involves specialization in a particular area, such as aircraft design, propulsion systems, or space exploration, leading to roles in research, development, or management. Medical career advancement typically progresses through residency and fellowship programs, leading to specialization in a specific area of medicine and potential leadership roles in clinical practice, research, or administration.

Ultimately, the perceived difficulty of either field is subjective and dependent on individual aptitudes, learning preferences, and career goals. A thorough self-assessment and realistic understanding of the demands of each discipline are crucial for making an informed decision.

The next section will delve into resources for further exploration of these career paths.

Concluding Remarks

The exploration of whether aerospace engineering presents a greater challenge than medicine reveals a nuanced landscape. While aerospace engineering demands a strong foundation in mathematics and physics, medicine necessitates extensive knowledge of biological systems and diagnostic capabilities. The difficulty is therefore contingent on individual strengths, aptitude, and the inherent attraction to the core principles of each discipline. Objective metrics, such as curriculum complexity and time commitments, reveal demanding workloads in both fields, precluding a definitive pronouncement of one being uniformly “harder” than the other. Instead, the analysis highlights the distinct rigor associated with the specialized knowledge and skill sets required for success in either profession.

Ultimately, the question “is aerospace engineering harder than medicine” lacks a universally applicable answer. Prospective students and professionals should prioritize a thorough self-assessment, aligning their inherent abilities and passions with the specific demands of each field. Careful consideration of the ethical responsibilities, long-term career trajectory, and personal fulfillment will guide a more informed decision, transcending the simplistic notion of comparative difficulty and emphasizing the intrinsic value of contributing to either the advancement of technology or the betterment of human health.