This field integrates scientific and technological principles to design, develop, test, and manufacture aircraft and spacecraft. It encompasses diverse areas such as aerodynamics, propulsion, materials science, structural analysis, and control systems. Applications extend from commercial airliners and military jets to satellites, rockets, and interplanetary probes. A prime example is the development of reusable launch vehicles, aimed at reducing the cost of space access.

The significance of this domain lies in its contributions to transportation, communication, national security, and scientific discovery. Advancements within it lead to faster and more efficient air travel, enhanced global connectivity through satellite technology, strengthened defense capabilities, and a deeper understanding of the universe through space exploration. Historically, it has spurred innovation across various industries, from lightweight materials to advanced computing.

The following sections will delve into specific aspects, including advancements in propulsion systems, the growing field of unmanned aerial vehicles, and the ongoing quest for sustainable and environmentally responsible aviation technologies. These are but a few examples of the continuous evolution within this crucial sector.

Guidance for Aspiring Professionals

The following insights aim to guide individuals pursuing careers that require expertise in flight vehicle design, development, and operation, within and beyond Earth’s atmosphere. Careful consideration of these recommendations may enhance preparedness and professional prospects.

Tip 1: Develop a Strong Foundation in Mathematics and Physics: Proficiency in calculus, differential equations, linear algebra, and physics is paramount. These disciplines provide the analytical tools necessary for understanding complex phenomena in fluid dynamics, thermodynamics, and structural mechanics. For example, understanding Navier-Stokes equations is crucial for analyzing airflow over airfoils.

Tip 2: Gain Practical Experience Through Internships and Research: Seek opportunities to apply theoretical knowledge through hands-on projects. Internships at aerospace companies or research positions at universities can provide invaluable experience in design, testing, and data analysis. Participation in projects such as designing a small-scale wind tunnel or developing a flight control algorithm will prove beneficial.

Tip 3: Master Relevant Software and Tools: Familiarity with industry-standard software, such as CAD (Computer-Aided Design) programs like CATIA or SolidWorks, CFD (Computational Fluid Dynamics) software like ANSYS Fluent or OpenFOAM, and programming languages like MATLAB or Python, is essential. Developing skills in these tools allows for effective simulation, analysis, and design of aerospace systems.

Tip 4: Specialize in a Specific Area: This field encompasses diverse specializations, including aerodynamics, propulsion, avionics, structures, and space systems. Focusing on a particular area of interest allows for in-depth knowledge acquisition and the development of specialized skills. For instance, one may specialize in hypersonic vehicle design or satellite communication systems.

Tip 5: Stay Abreast of Technological Advancements: This sector is characterized by rapid technological innovation. Continuous learning is crucial for staying current with the latest developments in areas such as advanced materials, additive manufacturing, electric propulsion, and artificial intelligence. Regularly read technical journals, attend conferences, and participate in professional development activities.

Tip 6: Cultivate Strong Communication and Teamwork Skills: Collaboration is essential for success. The ability to effectively communicate technical information, work collaboratively on multidisciplinary teams, and present findings clearly is highly valued. Participate in group projects, practice technical writing, and develop presentation skills.

Tip 7: Pursue Advanced Education: A master’s degree or doctorate can enhance career prospects and open doors to research and leadership positions. Advanced studies provide opportunities for in-depth specialization, research experience, and the development of expertise in emerging technologies. Consider pursuing advanced degrees in areas like aerospace engineering, mechanical engineering, or physics.

These recommendations offer a pathway to a fulfilling career. By focusing on foundational knowledge, practical experience, and continuous learning, aspiring professionals can contribute to the advancement of flight vehicle technology and push the boundaries of exploration.

The subsequent sections will explore specific technological areas, highlighting ongoing research and development efforts. These examples illustrate the dynamic nature of the field and the opportunities for future innovation.

1. Aerodynamics

Aerodynamics forms the bedrock of aircraft and spacecraft design, directly impacting performance, stability, and fuel efficiency. Its principles dictate how air interacts with moving objects, a critical consideration in the development of any flight vehicle. The effective application of aerodynamic principles is fundamental to the success of any aerospace project.

- Lift Generation

The primary function of an airfoil is to generate lift, the force that opposes gravity and enables flight. The shape of the airfoil, typically curved on the upper surface and relatively flat on the lower surface, creates a pressure differential, with lower pressure above the wing and higher pressure below. This pressure difference results in an upward force, allowing the aircraft to ascend and maintain altitude. Optimizing lift is essential for efficient flight and reducing takeoff distances. For instance, high-lift devices such as flaps and slats are deployed during takeoff and landing to increase the wing’s lift coefficient.

- Drag Reduction

Drag is the force that opposes the motion of an aircraft through the air, consuming energy and reducing speed. Aerodynamic design aims to minimize drag through streamlining and careful shaping of the aircraft’s surfaces. Different types of drag, such as skin friction drag and pressure drag, require specific mitigation strategies. Laminar flow airfoils, for example, are designed to maintain smooth airflow over a larger portion of the wing’s surface, reducing skin friction drag. Winglets at the wingtips are used to reduce induced drag by minimizing wingtip vortices.

- Stability and Control

Aerodynamic forces and moments play a crucial role in maintaining stability and control. Control surfaces, such as ailerons, elevators, and rudders, are used to manipulate these forces and moments, allowing the pilot to steer the aircraft. The stability of an aircraft is determined by its tendency to return to its equilibrium state after a disturbance. Aerodynamic design considerations, such as the placement of the center of gravity and the size and shape of the control surfaces, are essential for ensuring stable and controllable flight. Aircraft that are inherently unstable, such as some fighter jets, rely on sophisticated flight control systems to maintain stability.

- Supersonic and Hypersonic Aerodynamics

At supersonic and hypersonic speeds, the behavior of air changes dramatically, requiring specialized aerodynamic considerations. Shock waves form, leading to increased drag and heating. Aircraft and spacecraft designed for these speeds, such as the Space Shuttle and hypersonic missiles, require sharp leading edges and carefully designed shapes to minimize the impact of shock waves. Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations and wind tunnel testing are essential for understanding and predicting the aerodynamic behavior of these vehicles at extreme speeds.

These aerodynamic principles are foundational to all aspects. Advances in computational methods and experimental techniques continue to refine the understanding and application of aerodynamics, leading to more efficient, safer, and higher-performing flight vehicles.

2. Propulsion Systems

Propulsion systems constitute a critical and enabling component within aerospace engineering. These systems generate the thrust necessary to overcome drag and propel aircraft and spacecraft through the atmosphere or space. The functionality and efficiency of these systems directly influence the performance characteristics, range, payload capacity, and overall mission feasibility of aerospace vehicles. The design, development, and integration of appropriate propulsion systems are therefore inextricably linked to the advancement of aerospace technology.

A diverse range of propulsion technologies are employed depending on the specific requirements of the aerospace application. Air-breathing engines, such as turbojets, turbofans, and turboprops, utilize atmospheric air as an oxidizer, making them suitable for aircraft operating within the Earth’s atmosphere. Rocket engines, on the other hand, carry both fuel and oxidizer, allowing them to function in the vacuum of space, as exemplified by the Space Shuttle’s main engines or the solid rocket boosters used for satellite launches. Electric propulsion systems, including ion thrusters and Hall-effect thrusters, offer high specific impulse for long-duration space missions, demonstrating their utility in deep-space exploration, such as the Dawn mission to the asteroid belt.

The continuous pursuit of improved propulsion technology is a defining characteristic of aerospace engineering. Efforts are focused on enhancing fuel efficiency, reducing emissions, increasing thrust-to-weight ratios, and developing new propulsion concepts, such as hypersonic engines and advanced rocket propellants. These advancements not only enable more efficient and sustainable air travel but also expand the possibilities for space exploration and utilization. The ongoing development of advanced propulsion systems remains a central challenge and a key driver of innovation in the broader aerospace domain.

3. Materials Science

Materials science forms an indispensable pillar of aerospace engineering. The performance, safety, and longevity of aircraft and spacecraft are fundamentally dictated by the materials from which they are constructed. The extreme conditions encountered in aerospace applicationshigh and low temperatures, intense stress, radiation exposure, and corrosive environmentsnecessitate materials with exceptional properties. Therefore, materials science is not merely a supporting discipline but an integral component in the design, development, and operation of aerospace vehicles.

The evolution of aerospace engineering has been directly tied to advancements in materials science. For instance, the transition from wood and fabric to aluminum alloys in aircraft construction significantly improved strength-to-weight ratios, enabling greater payload capacities and longer flight ranges. The development of high-temperature alloys, such as nickel-based superalloys, has been critical for the efficient operation of jet engines, allowing for higher turbine inlet temperatures and increased thrust. In spacecraft design, materials like titanium and carbon fiber composites are used extensively for their high strength and low weight, vital for minimizing launch costs and maximizing performance in the harsh environment of space. The Space Shuttle, for example, relied heavily on ceramic tiles for thermal protection during re-entry, safeguarding the vehicle from extreme heat generated by atmospheric friction.

The future of aerospace engineering is inextricably linked to continued innovation in materials science. Ongoing research focuses on developing lighter, stronger, and more durable materials, including advanced composites, functionally graded materials, and self-healing materials. These innovations promise to enable more efficient aircraft, more robust spacecraft, and entirely new possibilities for space exploration. The challenges are significant, requiring interdisciplinary collaboration between materials scientists, engineers, and manufacturers to translate laboratory discoveries into practical aerospace applications, ultimately pushing the boundaries of flight and space travel.

4. Structural Integrity

Structural integrity is paramount within aerospace science and engineering. It ensures that aircraft and spacecraft can withstand the stresses encountered during operation, including aerodynamic forces, pressure differentials, thermal loads, and vibrations. Maintaining structural integrity is critical for safety, performance, and mission success.

- Load Analysis and Design

Accurate assessment of potential loads is the first step in ensuring structural integrity. This involves considering static loads, such as weight and pressure, as well as dynamic loads caused by turbulence, maneuvers, and engine vibrations. Finite element analysis (FEA) is extensively used to simulate stress distribution and identify potential weak points in the structure. For example, wing structures undergo rigorous FEA to determine their ability to withstand maximum aerodynamic loads during flight.

- Material Selection and Testing

The choice of materials directly influences structural integrity. Aerospace structures often employ high-strength, lightweight materials such as aluminum alloys, titanium, and composite materials. These materials are subjected to extensive testing to determine their mechanical properties, fatigue resistance, and environmental degradation characteristics. For example, composite materials used in aircraft fuselages undergo rigorous testing to ensure they can withstand repeated stress cycles without cracking.

- Damage Tolerance and Inspection

Even with careful design and material selection, structures can be susceptible to damage from fatigue, corrosion, or impact. Damage tolerance design ensures that the structure can withstand a certain amount of damage without catastrophic failure. Non-destructive testing (NDT) methods, such as ultrasonic testing, radiography, and eddy current testing, are used to detect cracks and other defects before they become critical. Regular inspections are crucial for identifying and addressing potential structural issues. For example, aircraft undergo routine inspections to detect fatigue cracks in critical components such as wing spars and landing gear.

- Structural Health Monitoring (SHM)

SHM systems continuously monitor the structural condition of an aircraft or spacecraft, providing real-time data on stress, strain, and damage. These systems use sensors, such as strain gauges and fiber optic sensors, to detect changes in the structural response, allowing for early detection of potential problems. SHM can reduce maintenance costs and improve safety by enabling condition-based maintenance. For example, SHM systems can be used to monitor the structural integrity of composite wings, detecting damage caused by bird strikes or lightning strikes.

These facets collectively contribute to maintaining structural integrity. Advancements in these areas are essential for enabling the development of safer, more efficient, and more reliable aircraft and spacecraft. Continued research and development in structural integrity are crucial for pushing the boundaries of aerospace technology and ensuring the continued safety of air and space travel.

5. Control Systems

Control systems represent a core enabling technology within aerospace science and engineering. Their function is to maintain stability, guide trajectory, and ensure precise operation of flight vehicles. The complexity of aerospace systems necessitates sophisticated control strategies to manage inherent instability and respond to dynamic environmental conditions. Failure of a control system can have catastrophic consequences, highlighting its critical importance.

One example is the flight control system of a commercial airliner. This system integrates sensors, actuators, and a control computer to manage aircraft attitude and trajectory. The control computer processes inputs from the pilot, inertial measurement units, and air data sensors to calculate control surface deflections necessary to achieve the desired flight path. The actuators, typically hydraulic or electric, then move the control surfaces, such as ailerons, elevators, and rudders, to generate the required aerodynamic forces and moments. Without precise and reliable control, an airliner would be unflyable. Similarly, spacecraft attitude control systems use reaction wheels, control moment gyros, or thrusters to maintain orientation in space, essential for communication, navigation, and scientific observation.

Advancements in control theory, sensor technology, and computational power continue to drive improvements in aerospace control systems. Adaptive control techniques, for instance, allow control systems to adjust their behavior in response to changing conditions or unexpected events. Model Predictive Control (MPC) optimizes control actions over a future time horizon, enabling more efficient and robust control. The development of fault-tolerant control systems, which can detect and compensate for component failures, is also a critical area of research. The ongoing refinement of control systems remains a central challenge, directly influencing the capabilities and safety of future aircraft and spacecraft.

6. Avionics

Avionics, a portmanteau of aviation and electronics, is an indispensable element within aerospace science and engineering. It encompasses the electronic systems used on aircraft, satellites, and spacecraft. These systems perform a wide array of functions, from communication and navigation to flight control and monitoring. The effective integration of avionics is critical for ensuring the safety, efficiency, and mission success of aerospace vehicles.

- Navigation Systems

Navigation systems provide accurate positional data and guidance for flight vehicles. These systems rely on various technologies, including inertial navigation systems (INS), global positioning systems (GPS), and radio navigation systems. INS uses accelerometers and gyroscopes to track movement and determine position without external references. GPS utilizes signals from a constellation of satellites to calculate position with high accuracy. Radio navigation systems, such as VHF omnidirectional range (VOR), provide directional guidance. The integration of these technologies enables precise navigation, even in challenging conditions, such as during instrument meteorological conditions (IMC). For example, an autopilot system uses navigation data to automatically steer an aircraft along a pre-programmed flight path.

- Communication Systems

Communication systems facilitate data exchange between the flight vehicle and ground stations, other aircraft, and satellites. These systems employ various communication protocols and frequencies, including VHF, UHF, and satellite communication. VHF is commonly used for short-range communication with air traffic control. UHF is used for military communications. Satellite communication enables long-range communication, including over-the-horizon communication. Reliable communication is essential for air traffic management, emergency response, and mission coordination. For instance, a satellite communication system enables astronauts on the International Space Station to communicate with mission control on Earth.

- Flight Control Systems

Flight control systems manage the stability and maneuverability of flight vehicles. These systems use sensors, actuators, and control algorithms to maintain desired flight parameters, such as altitude, airspeed, and heading. Fly-by-wire systems replace traditional mechanical linkages with electronic signals, enabling more precise and responsive control. Automatic flight control systems (AFCS), or autopilots, automate many aspects of flight, reducing pilot workload and improving safety. For example, a fly-by-wire system allows a pilot to execute complex maneuvers with greater precision and stability.

- Monitoring and Display Systems

Monitoring and display systems provide critical information to the flight crew about the vehicle’s performance, environment, and systems status. These systems include cockpit displays, such as primary flight displays (PFD) and multi-function displays (MFD), which present data on airspeed, altitude, attitude, engine performance, and navigation. Monitoring systems also track the health and status of various aircraft systems, such as engines, hydraulics, and electrical systems. This information enables the flight crew to make informed decisions and respond effectively to potential problems. For example, a PFD provides a clear and concise presentation of essential flight information, improving situational awareness and reducing pilot workload.

These examples underscore the essential role of avionics. Continued advancements in microelectronics, sensor technology, and software engineering will further enhance the capabilities and reliability of avionics systems, enabling safer, more efficient, and more capable aerospace vehicles. The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning into avionics systems holds the promise of autonomous flight and enhanced decision-making capabilities, further blurring the lines between human and machine control.

7. Space Environment

The space environment exerts a profound influence on all aspects of aerospace science and engineering. It presents a unique set of challenges that must be addressed in the design, construction, and operation of spacecraft and satellites. Understanding these challenges is critical for ensuring mission success and long-term reliability.

- Vacuum

The vacuum of space presents several challenges. The absence of atmosphere can cause outgassing of materials, potentially contaminating sensitive instruments and affecting thermal control systems. The lack of air also eliminates convective heat transfer, making thermal management more complex. Spacecraft must be designed to withstand these effects through careful material selection and robust thermal control systems. For example, satellites use multi-layer insulation (MLI) to minimize heat loss and maintain stable operating temperatures.

- Radiation

The space environment is permeated by high-energy particles, including cosmic rays, solar wind, and trapped radiation in the Earth’s radiation belts. These particles can cause damage to electronic components, degrade solar panels, and pose a health risk to astronauts. Spacecraft must be shielded from radiation using materials such as aluminum, titanium, and polyethylene. Radiation-hardened electronics are also used to minimize the effects of radiation damage. For instance, the International Space Station employs shielding to protect astronauts from harmful radiation.

- Micrometeoroids and Orbital Debris

Micrometeoroids and orbital debris pose a collision hazard to spacecraft. Even small particles can cause significant damage at orbital velocities. Spacecraft are designed with shielding to protect critical components from impacts. Tracking and avoidance maneuvers are also used to mitigate the risk of collisions with larger debris objects. For example, the Space Shuttle had debris shields to protect against micrometeoroid impacts, and collision avoidance maneuvers are routinely performed to avoid orbital debris.

- Temperature Extremes

Spacecraft experience extreme temperature variations due to direct sunlight, shadow, and internal heat generation. These temperature extremes can cause thermal stress, material degradation, and component failures. Thermal control systems, including heaters, radiators, and insulation, are used to maintain stable operating temperatures. For example, satellites use radiators to dissipate excess heat into space and heaters to maintain minimum operating temperatures during periods of eclipse.

These environmental factors necessitate specialized design and operational considerations. The successful navigation of the space environment underscores the integral role of aerospace science and engineering in enabling the exploration and utilization of space.

Frequently Asked Questions

The following questions address common inquiries regarding the discipline, providing clarity on its scope, career paths, and associated challenges.

Question 1: What distinguishes aerospace science and engineering from other engineering fields?

Aerospace science and engineering specifically focuses on the design, development, and operation of vehicles capable of flight within and beyond Earth’s atmosphere. It integrates principles from mechanical, electrical, materials, and computer engineering, but with a specialized emphasis on aerodynamics, propulsion, and space environment considerations.

Question 2: What are the primary areas of specialization within aerospace science and engineering?

Specialization areas include aerodynamics, propulsion systems, structural analysis, control systems, avionics, and space systems engineering. Each area requires specific expertise and knowledge related to the design, analysis, and testing of aerospace components and systems.

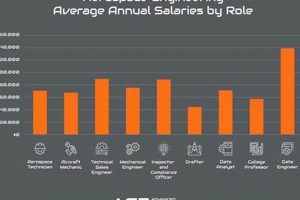

Question 3: What are the typical career paths for graduates with degrees in aerospace science and engineering?

Graduates pursue careers in aircraft and spacecraft design, research and development, testing and evaluation, manufacturing, and project management. Employment opportunities exist within government agencies, aerospace companies, research institutions, and consulting firms.

Question 4: What are the key skills required for success in aerospace science and engineering?

Essential skills include a strong foundation in mathematics and physics, proficiency in computer-aided design and analysis tools, problem-solving abilities, teamwork skills, and effective communication. A commitment to continuous learning is also critical due to the rapid pace of technological advancements.

Question 5: What are the major challenges facing the field of aerospace science and engineering?

Significant challenges include reducing the cost of space access, developing sustainable aviation technologies, mitigating the impact of orbital debris, and designing systems capable of withstanding extreme environmental conditions. These challenges require innovative solutions and interdisciplinary collaboration.

Question 6: How does aerospace science and engineering contribute to society?

Contributions include advancements in air transportation, global communication via satellites, national security, scientific discovery through space exploration, and technological spin-offs that benefit other industries. The field drives innovation and enhances the quality of life on Earth.

In summary, aerospace science and engineering is a complex and demanding field that offers opportunities for innovation and contribution to societal progress. A solid educational foundation, practical experience, and a commitment to lifelong learning are essential for success.

The following section explores emerging trends and future directions, highlighting areas of ongoing research and development.

Conclusion

This article has explored the core tenets of aerospace science and engineering, encompassing its fundamental principles, diverse applications, and the challenges inherent in operating within both atmospheric and extraterrestrial environments. Key areas such as aerodynamics, propulsion, materials science, structural integrity, control systems, avionics, and the impact of the space environment have been examined. The information provided underscores the complexity and interdisciplinary nature of this field.

Continued advancement hinges upon sustained investment in research and development, fostering collaboration between academic institutions, government agencies, and private industry. The pursuit of innovative solutions to challenges such as sustainable aviation, affordable space access, and enhanced mission capabilities remains paramount to ensuring the continued progress and societal benefit derived from aerospace science and engineering.